How to Gain More from

your Connection to an OT Network

One of the most productive and non-intrusive tools in the Cyber Security

Engineer’s bag is passive Network Traffic Analysis (NTA). Providing

network maps, inventory, and firmware information among other benefits provides

insights that are not generally known any other way. Manual inventory

collection methods are error-prone and expose this information to interception

over corporate email networks, shared file folders, etc. But how do we

implement this kind of system without causing any bumps in the road for

real-time processes? What are the risks? Which methods are

best? The best sensor does no good unconnected and is of little value

connected in the wrong part of the network.

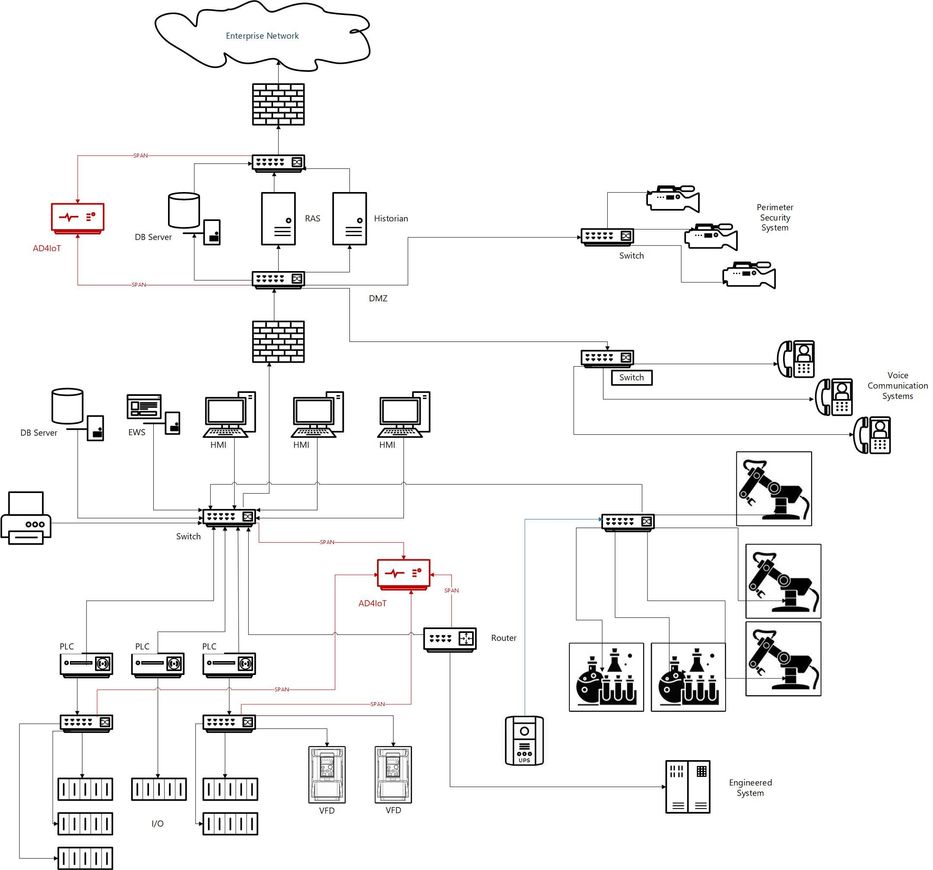

To discuss this, I will use a diagram that was developed

for my last blog post Designing a Robust Defense for Operational Technology Using

Azure Defender for IoT (microsoft.com). This diagram (below) shows an

example OT network monitored by Azure Defender for IoT.

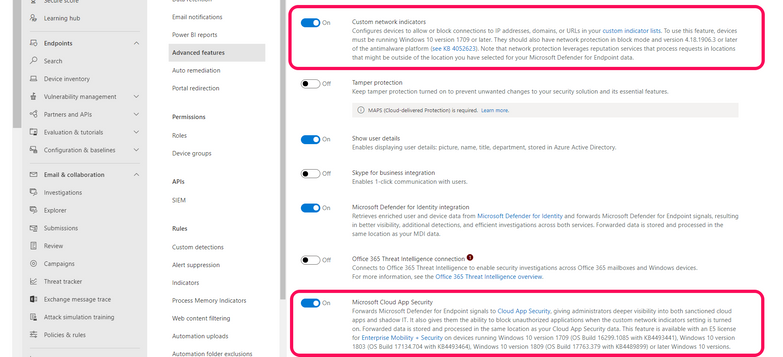

Defender for IoT is an agentless passive Network Traffic Analysis

tool with strong roots in Operational Technology, now expanding to IoT.

Defender for IoT discovers OT/IoT devices, identifies vulnerabilities, and

provides continuous OT/IoT-aware monitoring of network traffic. The

recommended locations for Azure Defender for IoT (AD4IoT) are shown in red color. Why have these locations been

chosen? To explain this, we will break this network into pieces and

address these issues for each type of traffic.

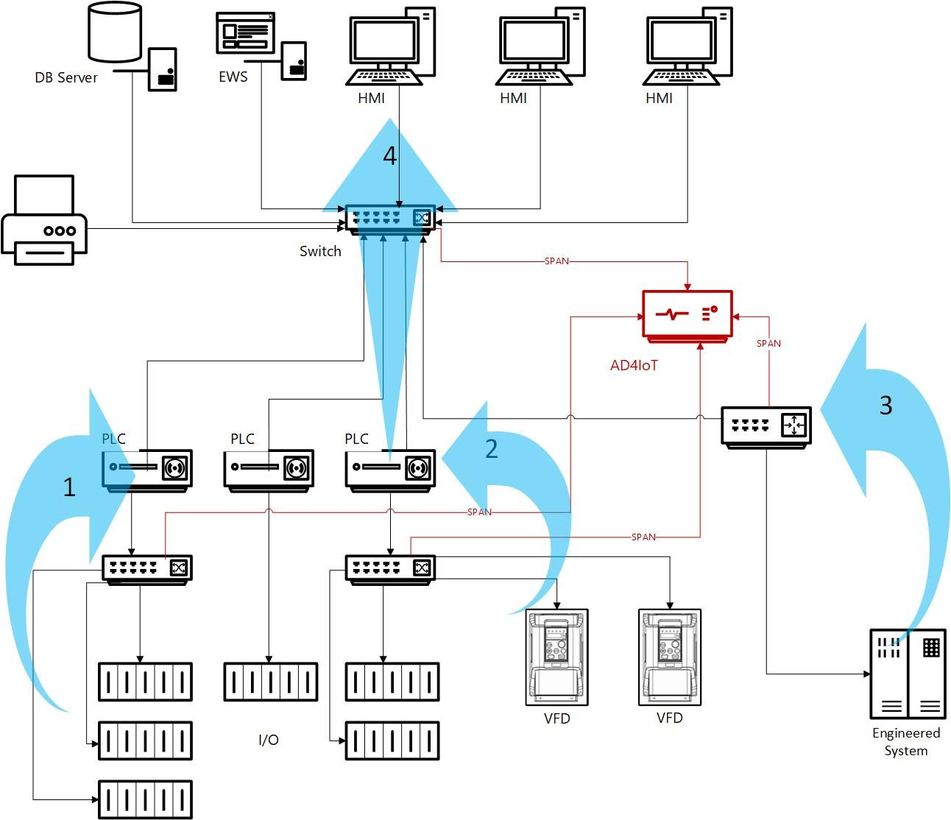

Starting with the lower portion of this sketch, let’s look at traffic flows

around the PLCs.

1. The first arrow shows traffic between

a PLC and its ethernet-connected Input/Output (I/O) modules. This traffic

utilizes simplistic protocols and is very structured and periodic. It can

be leveraged as a threat to the overall OT system and is more vulnerable when

I/O is remote from the PLCs in unsecured areas. Malicious applications

could perform inappropriate control actions and/or falsify data. Firmware

problems in I/O modules often go unpatched unless some form of undesirable

behavior is experienced. In certain families of PLCs or controllers, the

Defender for IoT can provide data on firmware levels and types of I/O modules

if this data is requested by an HMI or historian.

The mechanism to monitor this traffic is

to span switches used in the I/O subsystem as shown here. If they are

unmanaged switches, taps may be located at the connection to the PLC or

controller.

2. The second arrow identifies traffic

from Variable Frequency Drives or similar equipment often interfaced with the

PLCs or Controllers. This communication may be Modbus, Rockwell Protocols,

or CIP. Equipment could be damaged or destroyed by inappropriate commands

sent to such devices. Good engineering practice would put bounds of

reasonability around all potential setpoints, but this may not be the

case. These protocols are well understood and in the public domain.

A man-in-the-middle attack could affect this type of equipment.

Monitoring these communications can identify inappropriate function calls,

program or firmware changes, and parameter updates. As above, switch span or

taps are the mechanisms to monitor this traffic.

3. Custom engineered systems may utilize

well-known, open OT protocols such as Modbus, OPC, or others. This

traffic should be monitored even if it is not fully understood as the behavior

patterns should be very predictable. It is common for these systems to

utilize unusual functions and atypical ranges for data. This is the

result of a developer reading a protocol spec with no actual field experience

with the protocol. Custom alerts can be configured and tuned based on the

nature of the data. Since such systems are engineered to order for a

specific purpose, the damage could have long-term implications on plant

production.

4. Traffic crossing OT Access-level

switches should always be monitored. This is the primary point at which

PLCs or controllers communicate with HMIs, engineering stations, and sometimes

historians. The problem here is that these switches carry the actual OT

control traffic. Any action that could compromise this traffic affects

the reliability of the OT system. Many switches at the I/O and access

layers may be unmanaged devices. By unmanaged, I mean that they are not

configurable and therefore cannot support a SPAN (or mirror) session.

Unmanaged switches is not an

insurmountable hurdle. Two possible paths may be followed from this

point. The least intrusive is to install network taps. The security

engineer should consult with the OT engineer on the most valuable locations for

taps. Since a stand-alone tap monitors only one data stream, the most

valuable assets (compromise targets) should be monitored. These would normally

be at least the engineering station, historian and/or alarms server (if

appropriate), and HMIs, particularly those with engineering tools

installed. If it is necessary to monitor all traffic, a tap aggregator

may be used.

Another approach would be to replace the

unmanaged switches with managed switches. This may sound daunting but

usually is not. Most managed switches are configured to “wake up” in a

basic mode which approximates an unmanaged switch. So replacement, while

requiring a system shutdown, can be accomplished rather quickly and have the

system up and functioning again. Once this is done, the configuration can

be added to provide basic security and copy traffic to a SPAN or mirror

port. Make sure these configurations are saved as most switches make

changes to operating memory which is not stored on power reset. It is

generally recommended to discuss this change with your OT support personnel

and/or OEM service engineers. They probably have some standard switch

configurations that they apply when a customer requests managed switches.

Additionally, they should be able to provide you with approximate bus speeds

needed to support OT traffic with mirroring.

What are the risks? In the case of switch SPAN (SwitchPort ANalyzer), or mirror

sessions, the only concern of serious significance is the current traffic level

on the switch. If a SPAN session is added to a heavily loaded switch, the

SPAN may drop packets because the SPAN session is a lower priority than actual

switching traffic. This could mean that some packets might slip through

unmonitored. However, it does not affect the normal functioning of the

switch for ICS traffic. Some switches, if they are greatly overloaded can

revert to ‘flood mode’ in which they act as a network hub. This situation

is extremely rare. If switch SPANning is chosen as a method, it is wise

to monitor network traffic on the switch prior to adding the session.

Assume that a full switch span will double the switch backbone traffic.

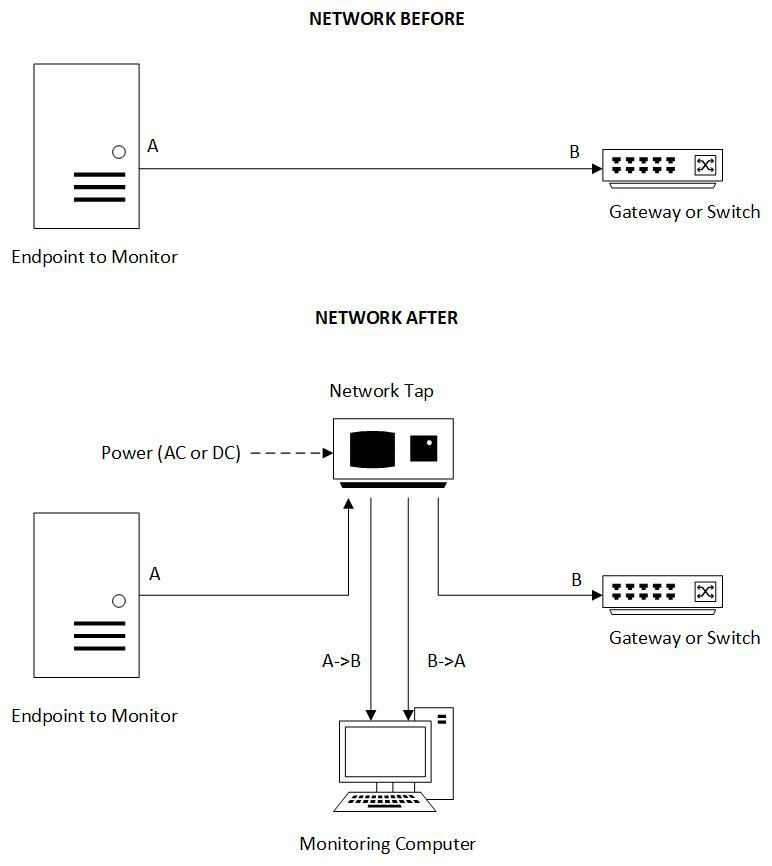

If network taps are installed, the risks are insignificant. Passive

taps should of course be chosen. Passive means that the tap continues to

pass control traffic even if it loses power. Passive taps are simply

inserted in-line with the existing traffic, see sketch below.

Installation needs to be coordinated with OT engineers to limit the impact on

operating processes.

Next, we will discuss special equipment including analysis devices and

robotics. This portion of the overall diagram is shown below.

Network traffic to analyzers typically looks like normal PC traffic using

common IT protocols. Most analyzers have some form of controller that is

designed for a specific function. Sometimes the PC is the

controller, utilizing specialized I/O boards included in the machine. Some

analyzers or groups of analyzers may be managed by mini computers.

In any case, from a network security perspective, these devices appear on the

network as computers, not analyzers per se. Patching of these customized

machines often lags behind the upgrade strategies used for standard IT

equipment. Upgrades to analysis systems must be approved by, and often be

implemented by the OEMs which may be expensive and involve downtime. Because of

infrequent patching and/or OS upgrades, this equipment can become a security

liability on a lab network. Ideally, lab equipment should be separated either

physically onto separate networks or via VLANs, but such changes may require

extensive planning and testing and still can be disruptive to ongoing lab

processes.

Most major medical laboratories utilize either a LIMS (Laboratory

Information Management System) or a middleware server to collect analytics data

from these devices and forward that data to a patient information database

managed either locally or in the cloud (see sketch below). Hence, the

traffic to/from the analyzer will be most easily recognized by the ultimate

destination at the middleware or LIMS. Since these potentially vulnerable

machines may process interactions with users on the lab network for input data

or maintenance functions, they should be monitored more closely than fully

patched IT machines. This presents a challenge to lab IT managers who may

want to gain a handle on this type of OT equipment in their network but may not

have good inventory information.

Since medical testing facilities utilize normal switched networks,

monitoring should be installed at an appropriate location to ‘see’ all the

traffic from analyzers to the middleware or LIMS server. This could be

either core or distribution level switches depending on the network

design. Standard SPAN or mirror traffic can be used.

Dual-homed machines present special security challenges since they could be

converted to active routers by malware. It is common for expensive lab or

analysis equipment to be leased. OEM terms and conditions specify how

this equipment may be used and what service it requires to achieve contracted

performance. This is often monitored via a ‘secure’ datalink to the

manufacturer’s support site. These may or may not be

bi-directional. These links are generally firewalled, either by the OEM,

by the customer or by both. Bi-directional links are inherently a threat.

Remote access to a computer on the lab network can put much more than that

computer in jeopardy.

In robotic applications, the primary issue is the speed of response.

The control systems are complex, utilizing high-level programming

toolsets. The low-level communication may not utilize standard ethernet

framing. Robot protocols vary widely and include Ethernet/IP, DeviceNet,

Profibus-DP, Profinet, CC-Link, and EtherCat protocols. Physical media

may be Cat5/6, but RG-6 coaxial, twisted pair, RS-485, and fiber are also

used. Monitoring the low-level communication between controllers and

robots requires careful coordination with the equipment designer and should not

be attempted casually. Network monitoring should utilize taps. Switch

SPAN, or mirroring is not recommended.

As described above, most industrial robots are programmed using a computer

workstation. Downloading and selection of programs may be manual or

automated using standard network protocols. So, monitoring should focus on the

programming workstations and the source of robot program selections.

Robot program file downloads may be transferred from a central server.

These could occur over SFTP, FTP, SMB, or other methods.

Finally, we would like to address the OT interface to the business

(Enterprise) network. This can be a gateway for potential threats to OT

systems. Some vulnerabilities that may be unsuccessful in the IT network

space may cause severe problems in the OT space because the machines may not be

patched. Out of date and unsupported operating systems may be in

use. As a result, traffic that enters from the Enterprise network and

ultimately reaches the OT network should be monitored.

Generally, good practice prevents any direct traversal of the DMZ. For

instance, remote desktop sessions should be hosted by a RAS server in the DMZ

which is then used to open a remote desktop session into an OT machine with

different credentials. Elaborate credential systems with short password lives

attempt to increase the challenge for attackers attempting to gain

control. Well designed implementations keep all machines in the DMZ

patched up-to-date which should limit the effect of known

vulnerabilities.

Zero day vulnerabilities will always be a threat prior to discovery.

So, monitoring sessions entering the DMZ from the Enterprise and those leaving

the DMZ for the OT network are an important part of a security design.

Similarly, monitoring traffic from the OT network to a Historian server and

Enterprise connections to that same server could uncover issues. Since

these sessions are often encrypted, efforts should focus on the legitimacy of

the Enterprise hosts, times of access, data rates, and other indicators to

validate these externally generated sessions.

The DMZ is also used as a connection point for a variety of other facility

systems such as IP phones; perimeter security systems; weather stations;

contracted supply systems like water purification, compressed air supply and

the like; wireless devices; etc. In most cases, these various systems are

assigned separate VLANs and subnets. By monitoring all the VLANS in this

zone, suspicious traffic can be identified and managed. Traffic

originating from any of these devices to the ICS network should not normally

exist.

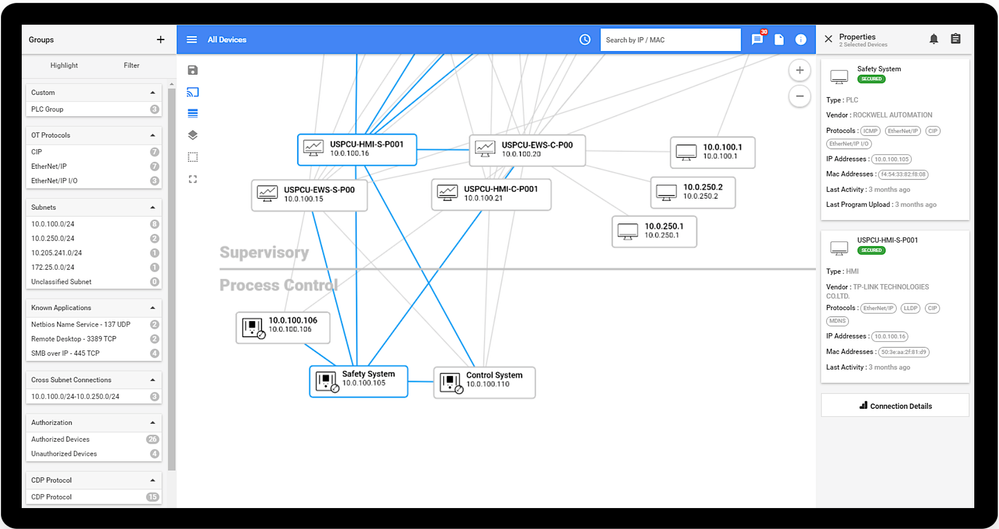

Subnet-to-subnet traffic could be cause for concern. This is another

area where Defender for IoT can help. By mapping the assets, assigning

them to VLANs, subnets, and user assigned subsystems, communication between the

various device groups can be easily seen greatly aiding efforts to perform or

monitor network segregation.

The visual network map produced by Defender for IoT in conjunction with the

filtering capabilities on the map make it easy to identify interconnections

between various plant control systems. Having a powerful visual of

group-to-group communication makes the effort of segmentation much

easier. This process is a long and tedious one using arp tables on

switches. Also, if this effort is underway, the map will show areas that

may have been overlooked.

Conclusions:

Well-engineered connections to ICS networks can yield valuable results,

including accurate inventories, network maps, and improved security with no

risk to the reliability of the underlying OT systems. This information

can be combined, in Azure Sentinel or other

SIEM/SOAR solutions, with agent-based Defender for endpoint data to produce a

complete picture of OT networks. Custom-designed playbooks can assist

your analysts in responding to OT or IoT issues.

Teamwork between OT engineers and IT security personnel can yield benefits

for both groups while presenting a more challenging landscape to potential

intruders.